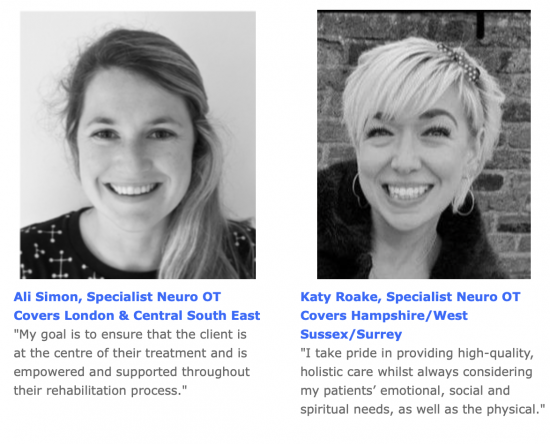

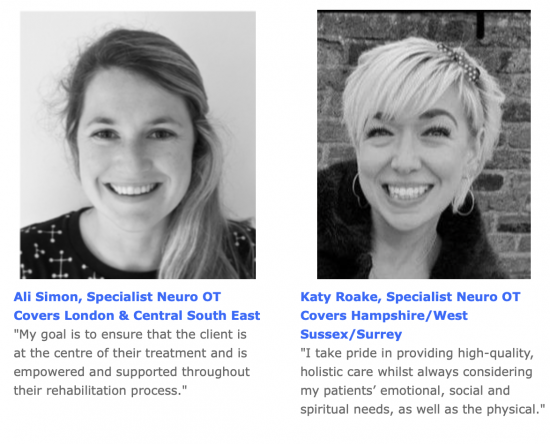

News from the LSOT neuro occupational therapy team

LSOT is supporting a new identity after brain injury factsheet produced by the charity Headway. The publication has been written to explain what identity is, how it can be affected by brain injury and how to cope.

LSOT’s Helen Harrison tells OT Magazine how supportive workplaces make a huge difference for patients on neuro occupational therapy programmes.

Brain injury fatigue is a common and persistent symptom of traumatic brain injury (TBI) characterised by an overwhelming sense of tiredness, lack of energy, motivation and mental clarity.

As neuro occupational therapists, we see brain injured people struggling with fatigue time and again but without a clear understanding of why.

TBI fatigue is caused by physical or cognitive changes in the brain caused by the head injury and can be exacerbated by stress, poor sleep, physical activity and other medical conditions. Brain injury fatigue is pathological and therefore different from ‘normal’ fatigue that everyone experiences at some point in their lives.

A report by brain injury charity Headway Managing fatigue after brain injury found 73% of people who had suffered TBI went on to experience fatigue afterwards. Most respondents (87%) reported fatigue as having a negative effect on their life while three-quarters said people around them did not understand why they were so frequently tired. Furthermore, 68% felt their romantic relationships had got worse as a result.

Beating fatigue through neuro occupational therapy

Through collaboration with a neuro occupational therapy team it is possible for TBI sufferers to accommodate fatigue after brain injury and not be dominated by it.

Fatigue management requires a mixed approach involving physical, cognitive and behavioural strategies. Our team of neuro occupational therapists work closely with brain injured people to develop individualised treatment plans that help them cope with their symptoms of fatigue and live fulfilling lives after TBI.

First we establish what their symptoms are, then develop awareness of the three types of fatigue – physical, cognitive and emotional – and advise on the best ways to combat the debilitating effects of fatigue. We’ve listed our most commonly-used neuro OT fatigue management tips below:

- Physical fatigue – Physical fatigue involves the inability to exert force with muscles to the level that would be expected. It may be an overall tiredness of the whole body, or confined to particular muscle groups. Physical fatigue most commonly results from physical exercise, loss of sleep or poor diet and can lead to mental fatigue.

OT tip: sit or lie down where possible, take catnaps or regular breaks; pay attention to the time of the day and the food you eat. It’s surprising how many TBI survivors underestimate their ability to carry on life as before and struggle to understand why their bodies don’t function like they used to.

- Cognitive fatigue is the most common form of fatigue suffered by survivors of brain injury but is often more difficult to recognise or measure. Reduced concentration, forgetfulness, communication or speech problems; many people struggle to find words or follow complex instructions, and slower processing speeds makes doing activities twice as long to complete.

OT tip: Take a brain break in a different context for 15-20 mins. We advise you do nothing at all with your brain in this time. Going for a walk or listening to quiet music can be perfect activities to recharge.

- Emotional fatigue is when people’s mood is affected and an individual can become more irritable, withdrawn or tearful. This is often detected more by the people living or working with a person with a brain injury.

OT tip: The best way to manage emotional fatigue is to help recognise the triggers for when you’ve maybe just done too much and really need to revert to a routine to help restore the energy. However, pleasure in life is underestimated and we encourage people to do more of what they like doing. If you’re an introvert, be alone for a while. If you’re sociable, see friends. Or take part in exercise or meditation, whatever works to boost your emotional state.

Knowing your 30% energy state

Our neuro occupational therapy programmes to help patients visualise their energy levels and manage fatigue. We often use a battery analogy to improve understanding of the condition, where zero percent is no energy and 100% is fully awake.

Fatigue rating works like an older phone battery; once you get to 30% the energy cuts out really quickly and needs an extra boost. Knowing what 30% looks like for an individual patient can help ensure they get the re-charge that is right for their needs and helps restore their brain power.

Redefining life after brain injury

The practical measures we’ve outlined have been developed by our neuro occupational therapists to support those struggling with brain injury fatigue to identify when their symptoms require a specific action.

If you’re a TBI survivor or a family member of someone who is, we hope this information and tips will help you see that there is hope. Your life does not need to be defined by your brain injury or dominated by your fatigue. As the Headway statistics demonstrate, there is an urgent need for more awareness, knowledge and understanding of TBI fatigue so people know they are not alone in their recovery journey.

Laura has a new PA, Sasha who is handling all new enquiries and referrals. Her details are admin@lsot.co.uk and 07563 310 605.

We’re always looking to expand our team of specialist neuro occupational therapists and rehabilitation assistants, so if you know of anyone suitably qualified and experienced who may be interested in working with us, please pass them our details or forward them this newsletter. We’d particularly love to hear from OTs and RAs who cover Essex, Kent and Surrey.

Please email Sasha at admin@lsot.co.uk

As part of LSOT’s neuro occupational therapy work with Brain & Mind, Laura contributed to the organisation’s Virtual Symposium on how to manage functional neurological disorder (FND). Specialists discussed the benefits of bespoke multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people suffering FND.

Brain & Mind combine neurology, neuropsychiatry and interdisciplinary rehabilitation therapies in treatment programmes for people with FND. The symposium looked at the challenges faced by patients trying to find quality ‘brain-mind’ integrated rehab programmes in outpatient and day patient settings (photo below).

Neuro occupational therapy and the importance of goal-setting

Setting goals is an extremely effective part of the neuro occupational therapy toolbox.

Goals help trigger new behaviours, guide focus and sustain momentum. They also help promote a sense of independence and self-mastery as well as track improvements during brain injury rehabilitation programmes.

Without goals, how will a patient know what progress they are making? How will we, as a team of neuro occupational therapists measure that progress?

According to Wade (2017), ”setting goals for patients is the central skill and process; without this skill, a clinician cannot deliver effective rehabilitation.”

Each small goal met is a building block to recovery. Measuring progress in this way enables a person to see that though they may not be where they would like straight away, they are heading in the right direction and are better off than when they first started.

All of us need to feel as if we are working towards something important and rewarding, that aligns with our personal values. Goal setting enables this and is a powerful motivator for people who have suffered brain injury.

Goal setting in action

An example of goal setting in action as part of LSOT’s neuro occupational therapy treatment programme can be seen in the case of one of our clients, a roofer who had fallen off a ladder.

As well as suffering a blow to his head, he had multiple orthopaedic injuries. Following his release from hospital he began having problems controlling his moods. He became volatile and struggled to complete the smallest of tasks. His injury took a toll on his marriage and his ability to be a hands-on father to his young twins and two older children. His wife said he had stopped helping with childcare and housework and was spending too much money and getting into debt. He was also putting himself at risk by attempting dangerous DIY jobs he could no longer manage. His balance had been badly affected by the accident.

Because he had metal plates in his leg, ankle and elbow, our patient saw his problems as being purely physical. He was dedicated to his physiotherapy but would exhaust himself and when on arriving home he was unable to do anything but sleep.

Like many of our clients at the beginning, he did not understand the point of neuro occupational therapy. However, once we explained how the process would work and discussed the merits of goal setting as a way of helping him back to a more fulfilling life, he was persuaded.

Goals setting in action

During our initial neurological occupational therapy assessment we discovered his hobby was car restoration. The last time he had worked on such a project was five years earlier. We presented the idea of a car restoration project to the client’s solicitor explaining how it would be a good way of gathering evidence of his problems which would assist his compensation claim.

His solicitor approved it as an OT project cost and we began the project.

One small step for man, one giant leap in recovery

We broke the car restoration project down into small, manageable chunks that we felt would be attainable goals.

Next we organised a care worker to act as a buddy to offer support throughout the project. Then we launched a staged activity analysis around a second-hand car we found on eBay.

Because the patient had been passed as safe to drive, he thought he would be able to fix the car and sell it for a profit. We gave him a fixed budget and asked him to carry out an assessment of the car to identify what actions were required to make it roadworthy.

One of the items on his list was to change the existing tyres. We asked could he repair the existing ones or would he need to buy a new set? He said he’d need new tyres which would be easy to accomplish. We agreed a deadline of four days to research and buy new tyres.

It took him three weeks. He had no idea how difficult he would find it.

He had not anticipated the exhaustion. Every time he turned the computer on to look at the internet he was overcome with fatigue. He used huge amounts of cognitive energy problem solving and generating ideas. He had to manage a controlled budget and delegate physical tasks to the buddy when he realised he could no longer do these himself.

Furthermore, he had not expected to lose concentration so easily or experience such difficulties with his memory. He found himself forgetting websites he had been looking at just a few minutes earlier.

Eventually he found a set of tyres and went to buy them only to discover there was not enough money left in his budget.

Identifying areas of weakness

By breaking the project down into a collection of small tasks, we were able to use a grading scale to measure the client’s insight as to the physical and cognitive challenge pre- and post-activity. This highlighted the areas where he most needed help.

In doing the practical tasks he realised for himself that his injuries were not just physical. The neuro occupational therapy treatment had helped him understand what areas he would need to adapt in order to optimise the way he lived. He saw that he would require wide-ranging support to sustain a quality of life. By the end of the activity we had not only identified areas where further work was required, but we had built good evidence of the client’s reduced capacity which would help in his claim for compensation to support his future levels of care.

In the early days of coronavirus lockdown No.1, I suggested to my neurological occupational therapy colleagues that we should try and see this enforced time away from the daily grind as a gift.

When do we ever get to stay at home so much? When are we likely to have an opportunity like this again to clear overflowing filing cabinets, CPD reflection sheets, old diaries and boxes of conference welcome packs?

All this time later, having been lucky enough not to have caught the virus, I feel a post-lockdown exhaustion I never for a minute anticipated at the start.

Much of it, I am certain, has been the effects on my brain of first, having to adjust to a radical lifestyle change and work pattern turned upside-down, and second, the processing of the constant overload of information about the infection: how it was spreading and killing; how it was being managed or not being managed.

As I tell clients, treat your brain well and it will function to its optimal ability. During the pandemic, I found adhering to that advice myself became a challenge.

A fresh insight into learning a new life

As an experienced neurological occupational therapist, I have a good understanding of the brain and the devastation wrought on lives when it cannot function as it should. For 27 years, I have worked with patients as they learn to adapt to new lives and rebuild as best they can under their new limiting circumstances.

The lockdown gave me a fresh insight into this and just how difficult it is to acclimatise to changes that make life so different to what’s gone before. This is not in any way to say I know what it feels like to have an acquired brain injury – I don’t. I only know what patients have told me: that it is frustrating, debilitating, distressing and overwhelmingly exhausting.

I have also heard many people use these same words to describe how they have experienced the coronavirus lockdown.

The advice to stay safe by remaining inside was so firmly pitted against the usual tips for achieving optimal mental and physical health, which is to be outside exercising or mixing with your community wherever possible. Everyone had to find ways of accepting their new reality and the powerlessness that had prevailed. At the same time, we had to keep our anxiety levels and fears about what was happening around us in check.

As well as learning to live differently, we had to learn to work differently. Like many independent occupational therapists in London, we discovered the magic of new technologies like Zoom, Teams, FaceTime and WhatApp in facilitating our sessions with patients, keeping in touch with colleagues and enabling us to hold team meetings remotely. On a personal level, these virtual platforms opened up avenues to reconnect with friends and distant relatives in the UK and overseas. We have been able to live coronavirus alongside them and hear their unique take of how the crisis is unfolding in their particular corner of the world.

Children and homework – but not as we know them!

The first change I made at the start of lockdown was to ensure my children were following the school routine. Naturally this meant incorporating their schedule into mine. Very soon it followed the school timetable, with breaktimes and PE played on a daily loop.

Pre-lockdown, my typical work day involved operating at maximum speed, rushing from one face-to-face meeting to another, seeing patients and always juggling competing priorities and commitments. At first it was refreshing to have a new routine that brought a sense of structure, activity, self-care and wellbeing into my life and that of my children. It was what has always been fundamental in my work as a neuro occupational therapist – setting schedules for patients to follow.

Being with my children so much was wonderful and frustrating in equal measure. There were highs and lows as all of us shifted our brains into a different gear and grew accustomed to the drastic lifestyle changes we were undergoing.

The always-on digital overwhelm

While the school day routine worked well at the beginning, it soon fell victim to the ‘always-on’ nature of digital media. Turning off WiFi in order to concentrate on report-writing was not an option; my children needed it to access their Google Classroom. And turning off the phone with so little formal office time, meant I’d often reach the end of the day with a mailbox full of voice messages needing to be addressed. Staying focused on the task at hand with so many demands and distractions pinging and beeping my way was not easy.

As the continuous stream of information, guidelines and health directives was released over the weeks and months of lockdown, my brain injury rehab team and I entered a new world of strict practices, risk assessments, PPE donning and indoor and outdoor interventions. We needed to learn the new expectations of referrers, case managers, nursing homes, colleagues and patients, as well as our own self-translation of the ‘new normal’. We drew on our empathy skills more than ever to remember that everyone now faced these same challenges in their own unique ways. Being kind at all times was paramount.

It’s hard to pinpoint the moment I realised the all-pervading digital creep had taken over and was now holding my school day routine hostage. I had succumbed to the 24/7 demands of new technology. While it has been a fantastic tool in allowing us to function as a team and continue to see our patients, it prompted new and unexpected requests for face-to-face or team sessions online.

My structured timetable was brought forward and pushed back and soon the work pattern was even more demanding than it had been pre-lockdown. On one occasion, I found myself scheduling a 22:30 video conference session with an Australian patient who had gone home to live through the crisis with his family. I was steeped in exhaustion and realised what was missing was downtime, that totally essential aspect of good brain health.

Reflection and rest time – healthy brain fundamentals in neuro occupational therapy

Pre-coronavirus, simple activities I used to do like driving between patient appointments, had provided valuable reflection time. Listening to the radio or having a natural change of activity would help me to process heavy workloads.

In the midst of the pandemic with so many new pressures, these valuable snippets of quality time to myself – the 101s of brain health – were so easy to overlook. There came a point where I felt as if my brain could not handle any more back-to-back virtual sessions, staring at computers and dealing with such intense cognitive communication demands. My energy levels were falling and I could feel the onset of burn-out. If one more social platform told me how to bake bread, grow my own vegetables or help me to fill my time I might just spontaneously combust.

My brain was saturated with information overload. It craved adequate reflection time in which to dry out. I knew I’d have to start practising what I preach and draw on the strategies I use with clients as part of the brain injury rehabilitation process. I needed to replenish my brain. I produced my own sleep hygiene and fatigue management plan and began to set aside time to let my mind simply wander.

Emerging into a post-lockdown lethargy

Towards the end of the lockdown, we emerged into a different world that felt fragmented and tense. Distance and alertness took on a new imperative over socialising and community mixing. It was a world where considering a life-preserving and healing holiday felt wrong. I have tried to analyse the guilt I felt over taking a break. Perhaps it was the effect of not having left my home in three months. Perhaps it was because I hadn’t seen my patients face-to-face.

Whatever the reason, I drew from the neuro occupational therapy and neurology techniques LSOT uses and reminded myself that taking breaks are good for mood, boost performance and increase ability to concentrate. They form an important part of a healthy life – whether it’s a holiday abroad or staying home and focusing on something very different for a while. Breaks are brain maintenance workshops in action – the place where your grey matter can hibernate from the exhausting endeavour of thinking.

Life lessons from lockdown

All of us as global citizens have had to fundamentally change the way we live, behave and relate towards one another in the home, workplace and community. This has required huge adjustments in our belief systems and values, as well as in the way we perceive the world around us.

While I have been lucky enough to be able to take my annual leave break and return with a brain that is fully recharged and ready for the next step, I know many people have not been as fortunate.

My boxes of conference welcome packs remain untouched. My filing cabinet is still creaking with old, disorganised resources while my computer hard drive continues to stare at me every day asking to be sorted.

But these things no longer feel as important. The ‘gift’ I referred to earlier has been to acknowledge, congratulate and celebrate the adaptability of the human being during such a challenging time. What a professional development 2020 has been.

Occupational therapy in London and the South East for brain injury rehabilitation

For more information call 07563 310 605 or click here to email

© Laura Slader Independent Occupational Therapy Services Ltd. 2020